|

Long, long before the PeakSoft Corporation were

flogging their software in the States, the original Peaksoft was offering

its quality products to the discriminating gentry in the UK. Now read

on....

A potted history of A potted history of

By HARRY

WHITEHOUSE

Back in 1981, I'd never really seen a

computer at close quarters for very long.

I used to administer the annual Mensa

competition for the newspaper in Burton-on-Trent for which I was then

working, and Mensa's president, a man called Clive Sinclair, donated the

first prize...a ZX81 home computer.

I tried to persuade myself that if I took it

out of the box for a quick test drive, the winner would never know. But I

chickened out.

In October, 1982, I spent £199 on a Dragon 32,

swayed by the advertisements for its "massive" 32k memory, and a keyboard

guaranteed to survive two million keystrokes. I also bought a couple of

pieces of software, written in Basic and saved on cassette tape. By the

time I'd read the manual, I'd decided that I could do better. (That's a

comment on the quality of the software, not on my ability.)

In common with many Basic programmers

before me, my first effort was an appalling hangman game, for which I

typed in a bank of 1,000 place names and 1,000 football topics. I had the

nerve to advertise it for £5.45 in Popular Computing Weekly and sold a few

copies. These were produced on the dining table with a Dragon and a

cassette recorder, then labelled with typewritten stickers. In common with many Basic programmers

before me, my first effort was an appalling hangman game, for which I

typed in a bank of 1,000 place names and 1,000 football topics. I had the

nerve to advertise it for £5.45 in Popular Computing Weekly and sold a few

copies. These were produced on the dining table with a Dragon and a

cassette recorder, then labelled with typewritten stickers.

I followed this up with Death's Head Hole (a

cave rescue simulation) and Lionheart, an awful low-resolution graphics

adventure. Both of these were sold through another advertisement, and by

writing to the people who had bought the hangman game.

Champions! Champions!

In the spring of 1983, I wrote a program which

was to change my life. It was a football management game. Because I knew

so little about programming, I kept it simple, with only four teams in

each division, and the crudest league table sorting imaginable. Addictive

Games had produced a very successful game called Football Manager for the

Spectrum, so I needed a different name, and I settled on Champions!

The cassette case insert had

a black and white Press photograph taken at Burton Albion's Southern

League ground. The cassette case insert had

a black and white Press photograph taken at Burton Albion's Southern

League ground.

By the judicious use of Tippex to obscure as

many clues as possible, I hoped no one would realise that the picture in

the Press advertisement was of the captain of a non-league team holding

aloft the league trophy.

In my innocence, I did not realise the

attractions of a football management game, and in its first advertisement,

in Your Computer, I gave it second billing to Death's Head Hole. However,

the orders, when they came, were for Champions!

The first cassette labels

were all hand-typed. The first cassette labels

were all hand-typed.

At this point, I nearly made a huge mistake.

Salamander Software, who despite the appalling quality of their software,

were the number two Dragon sellers to Microdeal, offered to market

Champions!, and I was very tempted. Fortunately, I resisted their

offer.

I needed a follow-up, and dashed off another

low resolution graphics adventure, called SAS. This one was the first to

feature a little machine code. I didn't understand a byte of it, but I

copied it from a magazine listing to simulate machine gun fire. I then

went away on holiday for two weeks, and on my return, I could not find a

single copy of SAS. It was rewritten from scratch in ten days.

Boots were the leading stockists of

Dragon computers, so I wrote to their head buyer. As a result, in November

1983 they ordered £27,000-worth of tapes from me. I bought a second Dragon

and set to work duplicating them. I sat up late at night, saving every

single ordered copy from those two computers. As I wasn't paying

professional duplicators, all but about £1,000 of that order was pure

profit. Boots were the leading stockists of

Dragon computers, so I wrote to their head buyer. As a result, in November

1983 they ordered £27,000-worth of tapes from me. I bought a second Dragon

and set to work duplicating them. I sat up late at night, saving every

single ordered copy from those two computers. As I wasn't paying

professional duplicators, all but about £1,000 of that order was pure

profit.

In the same month, my employers were taken

over, and the new owners wanted to give my job to one of their employees

on another newspaper. I accepted a few thousand pounds to go away

quietly.

As soon as I returned home (this had all

happened within the space of a few hours) I started looking for another

job, but after mulling it over for a few days, my wife Maureen and I

agreed that I should spend two months seeing if I could make a full-time

job of Peaksoft.

A friend of mine, Gordon Smith, had a BBC

Model B computer. (When Acorn produced the BBC machine, they intended that

the main one should be their £299 Model A, with 16k RAM, as, in one of the

most misjudged Press statements of all time, they said: "Few home computer

users will ever require to use more than 16k.") The public felt otherwise,

and the 32k £399 Model B was the top seller.

Gordon rewrote Death's Head Hole for the BBC,

and I advertised in the local newspaper to recruit someone to rewrite it

for the 48k Spectrum. Both Gordon and the chap who did the Spectrum

rewrite worked on a royalties-only basis. At the time, I couldn't accept

that the bubble would not burst very quickly, and I was squirrelling away

every penny possible, rather than investing in new machines

myself.

Soon after, we moved to Queen Street,

Balderton, Nottinghamshire, which was to remain the home of Peaksoft. A

spare bedroom was changed into an office, and the entrance to the integral

garage was bricked up to provide a storeroom with access from the

house.

I began advertising in Dragon User magazine,

which brought in more customers, and four people submitted their own games

to me - one was a simple machine code game called Ossie, featuring an

osprey which had to catch fish by diving into a pool, another other was a

horse-race simulation, which I named Photo-Finish, the third was a package

of two text adventures, which I called Don't Panic!, and the fourth was a

ZX81 machine code game, Octopussy, which, amazingly, needed only 1k of

Ram.

As a result of the appearance of this page, I

received an email from Tony Evans, the programmer of Photo-Finish, who

emigrated to South Africa, where he now supplements his income with a

horse race result prediction service.

Two great

characters

Among the rewards in running Peaksoft were the

opportunities it gave me to meet some wonderful people. Leading the pack

were two great characters, Tim Love, and Martin Cleghorn (of whom more

later).

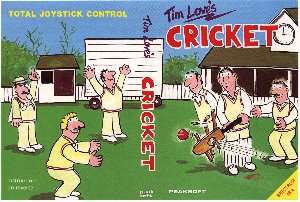

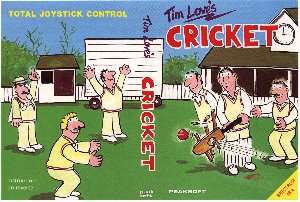

Tim had been on holiday in India. On the

long flight back, he began coding a game which I always regarded as a work

of genius, and which I called, quite simply, Tim Love's

Cricket. Tim had been on holiday in India. On the

long flight back, he began coding a game which I always regarded as a work

of genius, and which I called, quite simply, Tim Love's

Cricket.

It came to me in the post, out of the blue,

and one of my real regrets is that I never managed to secure for Tim the

rewards his work deserved.

Most of the coding for the Dragon game was in

Basic, but he managed to write a cricket game in which batting, bowling

and fielding were under joystick control, using very impressive batting

graphics. For its time, it set a precedent, providing Dragon owners with a

cricket game far better than anything available on the Spectrum or

Commodore 64, the machine's more popular competitors. Home Computing

Weekly awarded it 100% for graphics, playability and value.

I was so impressed with the game that I

invested heavily on the packaging and presentation. Unfortunately, the

chain retailers had begun to realise that their expectations for the level

of Dragon software sales had been unrealistic, so it never appeared on the

shelves of Boots, WH Smith and John Menzies.

Tim made one slip in the programming, and my

bug-testing failed to spot it before I started shipping the game. By

hitting the ball in a certain way, it was possible to make it go through

the boundary. Unfortunately, fielders could not pass through the boundary,

so the player was stuck, unable to continue with the game.

This was soon solved, but not before my

wife, Maureen, and I began to dread the ringing of the telephone.

Everyone, it seemed, wanted to tell us that their ball was stuck on the

wrong side of the boundary. This was soon solved, but not before my

wife, Maureen, and I began to dread the ringing of the telephone.

Everyone, it seemed, wanted to tell us that their ball was stuck on the

wrong side of the boundary.

I introduced a further problem. Tim had used

several USR calls, and when the Dragon 64 was introduced, the syntax was

changed. In my innocence, I did not know that a single line of code wouldl

enable the program to distinguish between the two machine, so I introduced

a line of Basic which read: "Do you have:

- 1 A Dragon 32

- 2 A Dragon 64

The intention was that the user should press

"1" or "2", which would then be interpreted by INKEY$.

Unfortunately, some users entered "32", to

indicate that they had a Dragon 32. INKEY$ rejected the "3", then accepted

the "2" as indicating that the machine was a Dragon 64. I learned very

quickly that bug-testing should always be done by people who do not know

how the program is supposed to work.

Tim assured me that the game made no Rom

calls. However, when I tried to convert it for theTandy Co-Co, I

discovered that this was a terminological inexactitude. As I had no

literature available, I started the mind-squelching task of searching

through the Co-Co Rom for sequences of code that were identical to those

called by Tim on the Dragon. I achieved it and sold precisely four

copies..

I did not meet Tim for several weeks after

receiving his game, but he moved from his native Portsmouth to Nottingham,

and we then came to know each other very well. He is now Computer Officer

for the Department of Engineering at Cambridge University which, I trust,

means that the massive royalties I failed to secure for him have not

proved to be of too great a consequence.

At that time, the credit card companies were

much stricter about allowing merchants - particularly mail order ones - to

use their services. In order that I could accept telephone orders, I

advertised a free cash on delivery service. This was very expensive, and I

have never seen a similar offer by any other firm. The Post Office insists

that any COD item is sent by registered post, so in all, it cost me almost

£3 for each COD copy I sent.

This was, however, better than making a sale

through a distributor. They, and major retail chains, demand a 55%

discount. Few people realise that when they pay £8.95 for an item (the

retail price of Tim Love's Cricket) it might have cost the vendor only

£3.50 + VAT.

I knew that the Dragon market was limited, so

I encouraged Tim to convert it to another format. He chose the Commodore

64, and promptly sat down to learn CBM64 assembler from scratch. I think I

had the finished game in my hands within about three months.

Having done that, he rewrote it for the

Amstrad CPC464. We had hoped to have a Spectrum version, but two separate

independent programmers wasted a lot of our time and eventually produced

nothing. Pictured is the insert card...ready for the game that was never

produced. Having done that, he rewrote it for the

Amstrad CPC464. We had hoped to have a Spectrum version, but two separate

independent programmers wasted a lot of our time and eventually produced

nothing. Pictured is the insert card...ready for the game that was never

produced.

The Boss

The obvious next step seemed to be

to develop Champions (I can't keep pedantically adding the exclamation

mark!) for other machines. I'd already rewritten it for the Spectrum and

the ZX81, and Gordon had adapted it for the BBCB.

However, I had finally figured out

how to do a passable sort routine, which allowed me to expand the number

of teams in a division from four to 12 (the maximum number that I could

fit on a Dragon screen) and so New Champions was born.

On the Spectrum, Commodore 64 and

Amstrad 464 (have Basic manual, will program!) I could now have 20 teams

per division, and with all that extra memory, there was no stopping

me.

To be accurate, the first version

- for the CBM 64 - of The Boss (as Champions was renamed for every

computer except the Dragon and the Tandy Co-Co) was written before I

discovered efficient sorting, so that had only four teams per division. I

overcame this handicap with great packaging, inserting the tape into a

card cut-out, which was fitted into a large box and colour sleeve,

together with a blank save game tape. The instructions were printed in

blue on glossy paper. It looked great, and it sold for £8.95.

For the first time, the tapes were

professionally duplicated, and not individually copied on my dining room

table. I didn't know anything about compression, so the program took eight

minutes to load.

Boots thought the box looked

wonderful, so I took lots more £3.50s off them.

The fact that the tapes were

duplicated did not mean, however, that my little cottage industry had no

part in the production. Each box was assembled by hand, and stuck together

with double-sided sticky tape, each tape was manually inserted, and each

instruction booklet was personally stapled by yours truly.

Versions of The Boss followed for

the many machines listed below. Throughout its very long sales life, it

was continually improved. The most feature-packed version was eventually

produced for the Spectrum, but I, my son and my daughter used to play it

until late 1996 on an Amstrad 664, which was slightly less complex, but

which played much faster. No one is quicker to rubbish my work than

myself, so I believe that entitles me to take some satisfaction from the

final versions of The Boss.

When retail shop

sales virtually ended, I still continued selling by mail order through

football magazines, then I made a few thousand pounds more by licensing

Alternative Software to issue budget versions. They renamed it Soccer

Boss, and for one wonderful week, it was number 1 in the UK sales

chart. When retail shop

sales virtually ended, I still continued selling by mail order through

football magazines, then I made a few thousand pounds more by licensing

Alternative Software to issue budget versions. They renamed it Soccer

Boss, and for one wonderful week, it was number 1 in the UK sales

chart.

The versions for machines other

than the Dragon had the very considerable benefit of a save game routine.

When I first wrote the Dragon version, I could not understand the manual's

instructions on data saving, so the early users suffered the frustration

of starting in Division 4 every time, or leaving their computers switched

on!

The shows

I loved the Dragon shows. The

first ones were run by Microdeal, the leading Dragon software house, at

the New Horticultural Halls, London. I used to hire a van (or on

occasions, just hitch a trailer onto my car) and drive down the previous

night. I would then sleep in the van/car, as a basic security

precaution...and because it was more fun that way.

Microdeal also organised one in

Manchester, but after that, most of the organising was to the credit of

John Penn, a mail order software retailer.

We had some excellent times at

Ossett Town Hall, Yorkshire (where I had a hard time persuading the

caretaker that he wouldn't get the sack for allowing me to connect my

Dragon to Prestel) and Cardiff Airport. John also organised a couple of

London shows, in which I was a sleeping partner, as the venues wanted

quite a large cash deposit.

My practice of travelling down the

night before and sleeping in the van caused a problem when John organised

a show at the Connaught Rooms in central London in December, 1987. When I

went to collect the hire van, I discovered to my horror that they had no

panel vans left, and the only available one had windows along both sides.

I parked in a busy London street, with boxes piled against the windows,

leaving a narrow alley in which I put my sleeping bag.

Usually, I ran my stand

single-handed, which meant that for a couple of hours in the mornings, I

was rushed off my feet, with irate people reasonably demanding to know

when I was going to serve them, while in the afternoon, I had no one to

talk to! At one show, I was helped by a police inspector called Gary, who

contacted me and volunteered his services on Prestel, and my daughter

Louise accompanied me to one of the Ossett shows.

Odds and ends take

over

It was at the shows that I began

to realise that people were more interested in buying odds and ends and

peripherals than software. I started to comb the market for cassette

leads, aerial leads, dust covers - anything, in fact, that a Dragon owner

might need.

Many youngsters, having bought a

Dragon, were disappointed to find that the joystick interface did not

support the switching type, which felt so much more satisfactory with

arcade-type games. There were several interfaces on the market, but as

with most Dragon suppliers, the people marketing them tended to come and

go, as the demand was too small to support such limited

specialisation.

I realised that by offering as

wide a range as possible of Dragon items, all of these small specialised

products could possibly add up to a worthwhile business.

I bought one firm's remaining

stock of printed circuit boards for joystick interfaces. I paid piecework

rates to two men, who had full-time jobs at a local electronics factory,

to build the interfaces in their spare time, first using the PCBs, then

copying the design manually onto pieces of board.

The Dragoniser was born. The

process was too expensive for me to be able to sell the interfaces at a

reasonable price, while making a profit, so I sold them only as complete

units with joysticks.

Many people began to experience

problems with the Dragon transformer. Some of these difficulties arose

through simple failure of the unit itself, and others through the

insecurity of the wiring in the plug that joined the transformer cable to

the Dragon. Wires tended to come loose and cause a short

circuit.

LEFT: Flan marks the sale of Tim Love's

Cricket to an Icelandic distributor.

In my innocence, I thought that I

could simply buy new transformers in bulk from a wholesaler, then pay my

moonlighters to bung them in plastic boxes and wire them up. However, I

soon discovered that the Dragon transformer is a rare beast, which must be

specially built and even finding suitable boxes took a week and cost a

fortune in telephone calls.

I discovered Douglas Electronics

in Louth, Lincolnshire, who, I learned, had built the Dragon Data disc

drive transformer, as well as the mains adapter for the Sinclair Spectrum.

The company told me that Dragon Data insisted on almost re-inventing the

wheel by designing the transformer from scratch, instead of using tried

and trusted designs, and that this had doubled the cost of the finished

product.

Douglas built new transformers for

the computer for me, in batches of 50. I was incapable of soldering the

cable to the Dragon's connector, so I farmed out the assembly work to

local moonlighters. I told Douglas that I wanted a transformer that with

luck, could never give cause for complaint. In the event, it worked

happily with the D32, D64 and Dragon Plus, and no claim was ever made

under the guarantee. I even managed to source a more satisfactory plug,

which did not either shear the wiring if it was too tight, or allow it to

be jerked out if it was too loose.

At the end of 1985, the Dragon

accessory business really took off. Sunshine Publications, who produced

Dragon User magazine, were left with thousands of £6.95 books that they

could not sell. They invited me to buy some, and I agreed to do so, on

condition that I could have them all, as I did not want anyone to undercut

me. We settled on the price of 10p a copy.

I had vaguely planned to store

them in my dining room, but on the night before they were due to arrive, I

awoke in the middle of the night with a terrifying premonition. I got up,

measured a book, multiplied this by several thousand, and discovered that

the consignment would fill the room five times over. Early next morning, I

rented space in a local warehouse, and redirected the juggernaut that was

delivering the books.

After a mail shot to existing

customers, I began selling them at £6.95 for five, post paid, and soon

recovered my outlay. The hundreds of left-over copies were eventually

covered with top soil and used to correct an inconvenient slope in my

garden. That should puzzle archeologists of the future.

Touchmaster, the successors to

Dragon Data, supplied me with potentiometer joysticks, which were

essential for Tim Love's Cricket and Microdeal's Worlds of Flight. I

became their sole outlet for these joysticks, and even supplied them as a

wholesaler to John Penn and my friend Harry Massey at

Computape.

Touchmaster had been trying to

sell a graphics tablet (of that name) for about £135. As might be

expected, there were few takers, so Touchmaster stopped production. I did

a deal which allowed me to take over their stock and sell the tablets

profitably for £35 each. I acquired these just in time for the 6809 Show

in London at the end of 1985, and sold all of the stock I had taken within

30 minutes.

In May, 1986, Touchmaster sent a

circular letter to Dragon dealers, inviting bids for their remaining stock

of uncased disk drives, spare keyboards, joysticks, software...the lot!

Peaksoft were by now the only firm with a sufficient breadth of interest

in the Dragon to contemplate making the financial investment that seemed

to be required.

Everyone else shied away, so I was

able to hire a lorry, drive it to South Wales, and fill it for less than

£1,800. As I had already arranged in advance to sell the software to a

dealer for £2,000, that was a very profitable day's work.

My knowledge of disk drives was

limited to knowing which hole to stick the disk in, so I definitely did

not want to be faced with any technical problems. To avoid this, I sold

the drives as door stops for £39.95 each, and advised purchasers that with

just a little good fortune, their door stop would turn out to be a

serviceable disk drive.

The keyboards - Dragon 64 type -

were also snapped up for £24.95.

Comms - 1986 style

Many people fail to appreciate

that computers were talking to each other long before the internet

revolution.

Back in the mid-1980s, we had

Micronet, Prestel and bulletin boards. Micronet had 400,000 pages,

accessible via a local phone call, using a 1200/75 modem. In case that

hasn't quite sunk in, that means we sent at 75 and received at 1200, as

opposed to today's common 33,600. British Telecom would not accept that

the equipment available to a home user was capable of sending at more than

75bps.

The system offered messaging

similar to email, and was very popular, until British Telecom killed it

stone dead by introducing a 1p a minute service charge.

I acquired some modems from a firm

called Modem House, together with a comms cartridge. When these ran out,

Martin Cleghorn, a bobby from the Lake District, contacted me. He designed

a new interface with a through cartridge port (to allow users to keep

their disk drive interfaces connected, for example). He wrote a program, I

bought him a gizmo to allow him to burn it onto an eprom, and we were off

and running again.

I became rather carried away, and

launched Radio Dragon. This was a very substantial electronic magazine,

stored on a 3-inch disk on an Amstrad CPC 664. At set times in the week,

Dragon owners could dial my telephone number, which would be answered by

the Amstrad. The magazine took about three minutes to download into RAM,

for viewing at leisure or saving to cassette. It was great fun while it

lasted (for six issues) but it was very hard work for no real return.

Martin wrote all of the software for the service.

By the end of 1986, we were

selling an extraordinary range of products for the Dragon. A Dragon User

advertisement of the time offers thermal printers for £59.95, modems,

joysticks, light pens, T-shirts, sweat shirts, car stickers (as shown at

the top of the page), books, power supplies, disk drive transformers,

aerial, cassette and printer leads, dust covers, data recorders, carry

cases, keyboards, magazines and monitors. We boasted: "We probably have

the world's largest range of Dragon accessories."

I made many friends among my

regular customers. One father and son wrote several upgrades of Champions

for the Dragon 64, and sent copies to me, and I had several gratifyting

exchanges of correspondence with other people.

Looking through my copies of

Dragon User, I am amazed to see how many firms came and went, often in the

space of a few months. One software house boasted in a Dragon User feature

that it was "number three behind Microdeal and Salamander". Three months

later, the partners saw me before a show in London in a state of

desperation, and I agreed to get them off the financial hook by buying

their entire stock of software for a knock-down price. I sold what I could

at the show, then sold the rest to John Penn at cost.

Power play

I heard that Commodore 64 power

supplies were proving rather unreliable, so I decided to investigate this

market. It was impossible to inspect the design of the originals, as they

were encased in resin, so I asked one of my moonlighters to design a new

one from scratch. His first attempt used a voltage regulator, which proved

unsuitable, but his next effort was a winner.

At the heart of it was a

transistor, and the design proved to be rermarkably reliable. The CBM64

used a non-standard plug for attachment to the computer, but I discovered

that it was possible to achieve the same result by pulling two of the pins

from a 7-pin DIN plug.

This power supply sold very well. I offered a two-year warranty

and a lifetime service guarantee, so it was advertised with the slogan:

"The last power supply you'll ever need - guaranteed!"

I recognised that the Dragon business was

running down, and I saw the diversification into power supplies as the

opportunity to maintain my independence. With simple ones - such as the

straightforward 9v units used by Spectrums, Commodore 16s and Electrons -

I could even trust myself to do the soldering!

One of my biggest single customers was a shop

in Leicester, called Cavendish Commodore Supplies. They suddenly wanted

200 units, and my faithful moonlighters simply couldn't produce them in

the time required.

I handed one of our power supplies to Douglas

Electronics, who were one of my transformer suppliers, and asked them to

build 200 to the same design.

Unfortunately, Douglas decided they knew

better, built them with voltage regulators, and then encased the internal

parts in resin. I was not aware of this, so I accepted the power supplies,

and sent them to Cavendish.

Within four weeks, they had all been returned

to me, as most of the first batch sold by Cavendish had failed, and,

understandably, they had no faith in the remainder.

Alan Sugar, meanwhile, had taken over

Sinclair, and he introduced the Spectrum Plus-3 - a Spectrum with a 3-inch

disc drive. There was a stereo socket to provide an interface for a taped

programs, and this provided another market opportunity for me, as there

were no leads available to link the stereo socket to the input and output

sockets on a cassette deck.

I had to get into the market before someone

imported a million from the Far East, so each lead was hand-soldered,

dropped into a freezer bag from rolls bought from local supermarkets, then

stapled to a card run off by a jobbing printer in his garden shed.

Surprisingly, the end product looked very good.

The end

As the figures below reveal,

business began to plummet in the late 1980s, simply because I could not

find anything to sell. In 1988, with a young family to support, I realised

I would have to sacrifice my independence, in order to secure a reliable

income.

The telephone stopped ringing

during the spring, and I decided to find a job after the school summer

holidays. Much of that year was spent self-indulgently cycling the local

country lanes, before a three week family holiday in France.

In September, I put my jacket and tie on again

and joined a local newspaper.

Peaksoft had provided me with a great deal of

fun. It paid off my mortgage and allowed me to invest enough money to help

my family to live a little more comfortably over the years.

If another chance arose tomorrow, would I take

it? Not half!

Meanwhile, if you ever see a car with a "I

love my Dragon sticker" in the back window (just like the one at the top

of this page), the driver will probably be me. So for old time's sake,

please give me a toot.

In 1999, the upstart (but rather rich)

PeakSoft of Massachusetts, USA, suddenly became aware that I had a prior

claim to the name - by about 15 years. They sent me an email, asking

rather anxiously if I intended to sue them, as they had already had to

change their name once after treading on another company's

toes.

I assured them that if they didn't call

themselves PeakSoft in the UK, I would turn a blind eye to their

usurpation of my trading name. But if I'm ever desperately short of a few

bob, maybe (just maybe) I'll think about hiring myself an American

lawyer!

I'm very much attached to the Peaksoft brand,

and I'm forever playing with ideas about new goods I could

market.

When we visited Istanbul, for example, I came

back with some a really good brass pepper mill (have you ever noticed that

most of the ones offered in the UK have useless plastic grinding wheels?)

I tried to find a supplier over the internet, but Turkish businesses don't

seem to be very switched on to the internet.

In February, 1999, we visited China, where I

found it was possible to buy silk ties for 40p each from street traders.

At home, I made contact by email with a couple of Chinese companies

willing to ship the ties, but only on terms that removed the attractive

price advantage. I think I'll have to go back with a few empty suitcases,

and you may then see Peaksoft ties appearing on sale.

Then in the Spring of 2000, I discovered Ebay,

the internet auction house. I'm having a great deal of fun, selling mainly

craft books and sheet music in auctions. I'll never be able to live on it,

but it gives me the satisfaction of earning all of my own personal

spending money. Peaksoft is going strong again!

Total sales

Software

HANG IT!

Dragon 182.

DEATH'S HEAD HOLE

Dragon 426, BBC B 312, Spectrum 90. Total

828.

LIONHEART

Dragon 5572

DON'T PANIC

Dragon 328.

SAS

Dragon 4066

CHAMPIONS!/THE BOSS

Dragon 8119, CBM64 7423, Spectrum 5645,

Electron 2333, C16/Plus 4 2028, MSX 1346, BBC B 1031, Amstrad 464/664 857,

ZX81 464, Oric 398. Total 29644.

OCTOPUSSY

ZX81 150

PHOTO-FINISH

Dragon 804, Tandy CoCo 11. Total

815.

OSSIE

Dragon 991, BBC B 171. Total 1162.

GULP!

BBC B 130.

TIM LOVE'S CRICKET

Dragon and Co-Co 4518, CBM64 1960, Amstrad

464/664 789. Total 7267.

Total software sales: 50144

Power supplies

| Dragon 367 |

CBM 64 1485 |

Spectrum 172 |

Electron 207 |

| C16 101 |

Plus-4 48 |

Misc 1 |

|

I'm still searching for statistics on sales of

joysticks, printers, modems and comms interfaces. I've got them

somewhere!

Tim

Love's page (DEAD LINK)

Email

me

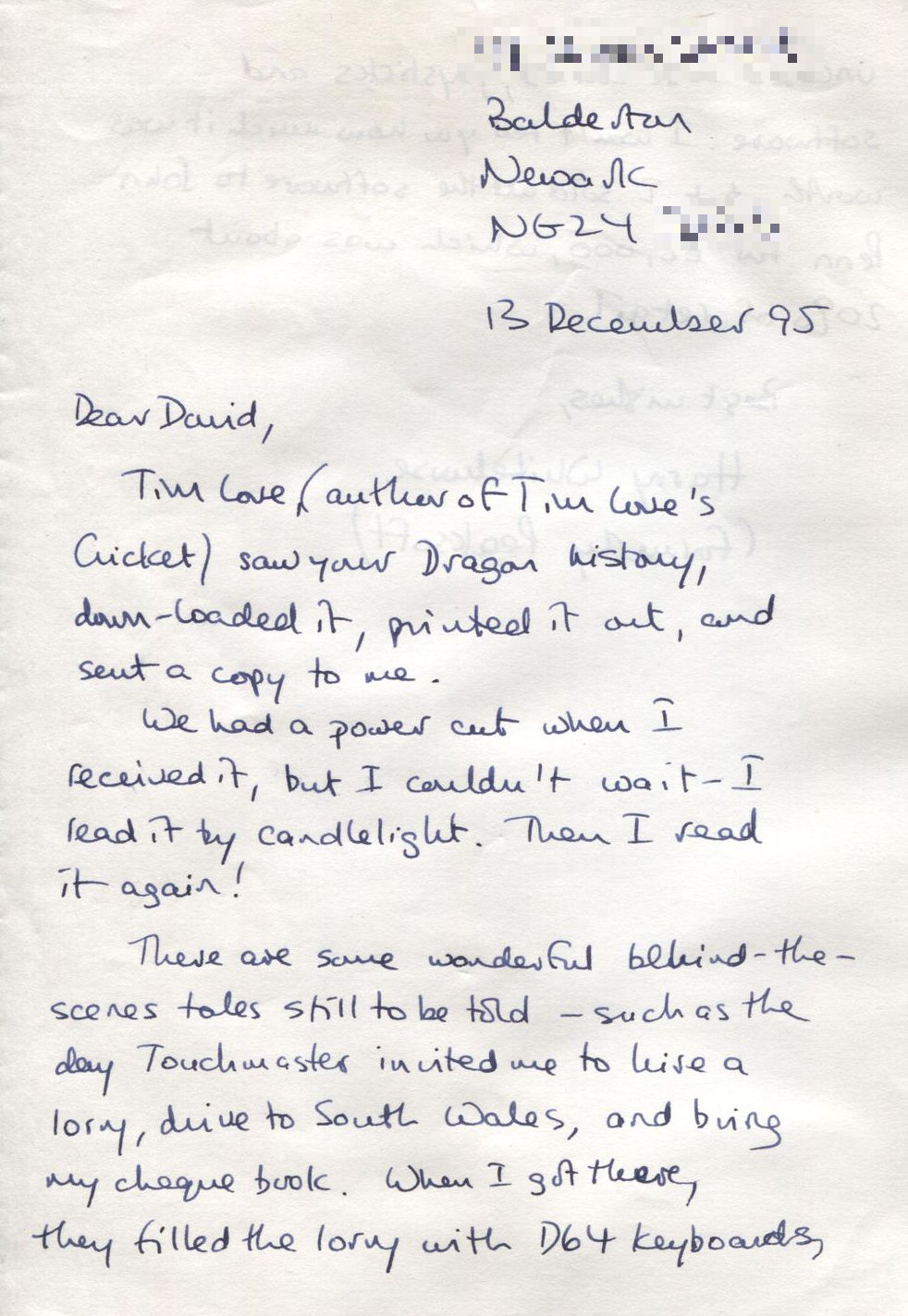

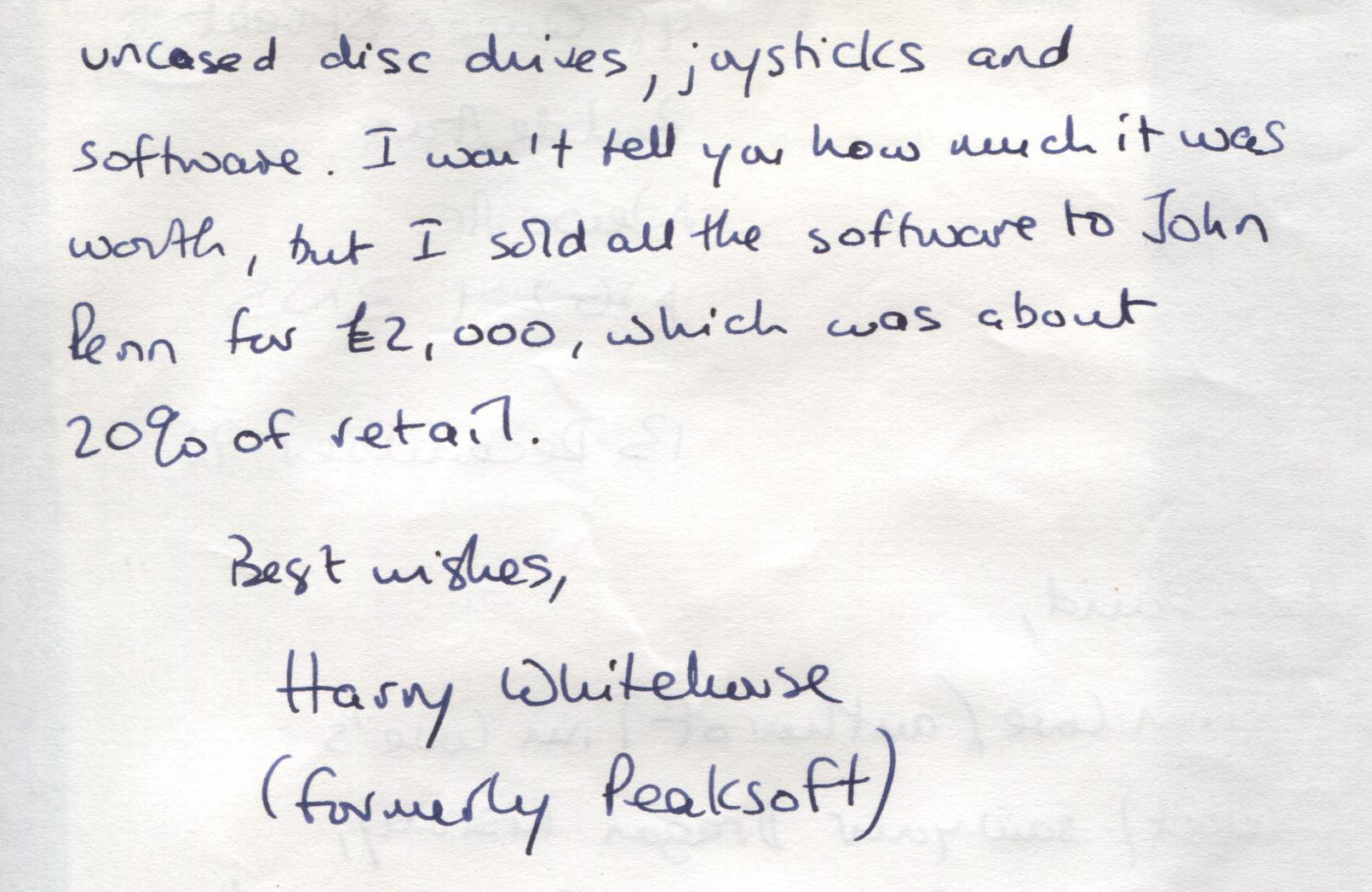

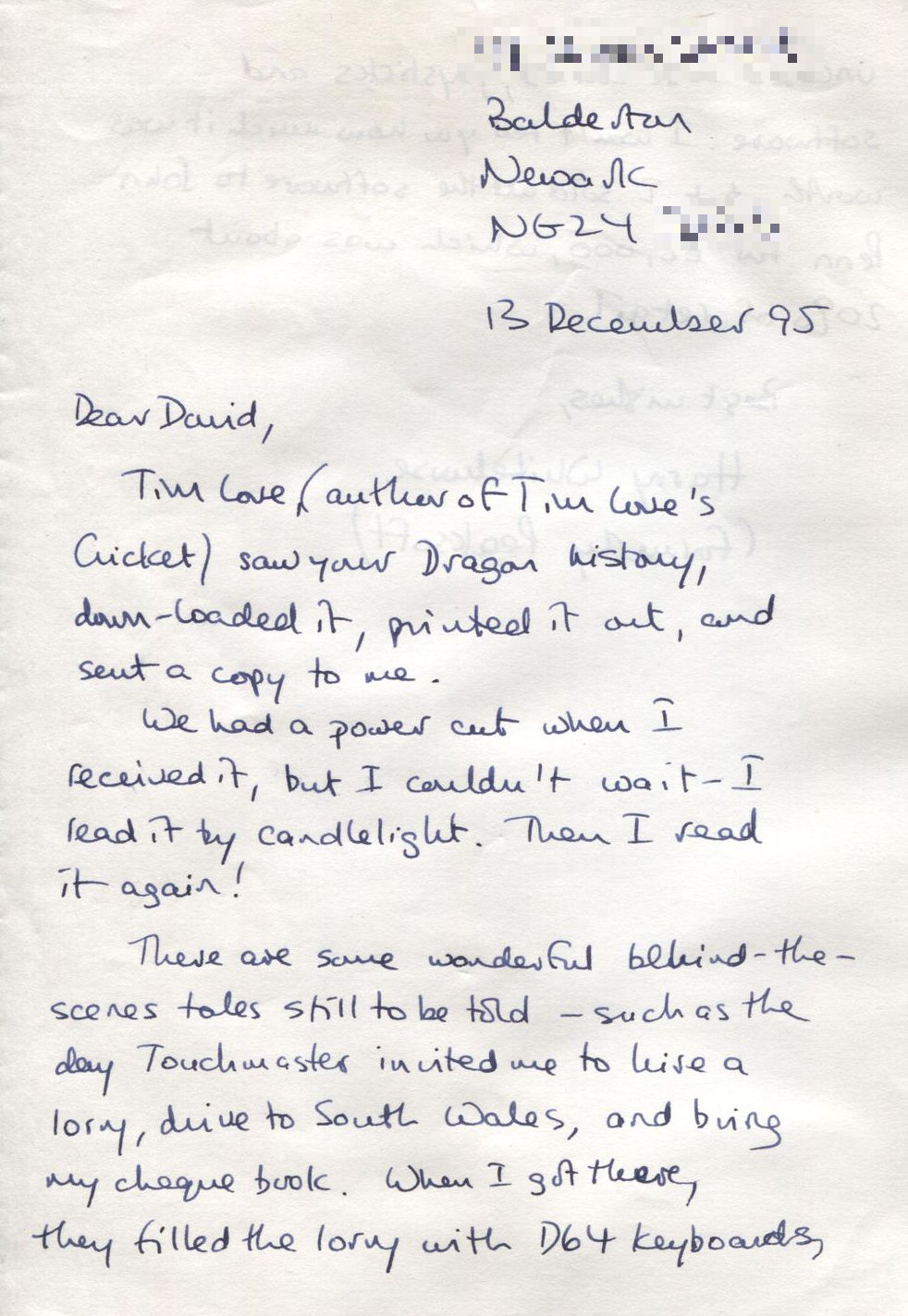

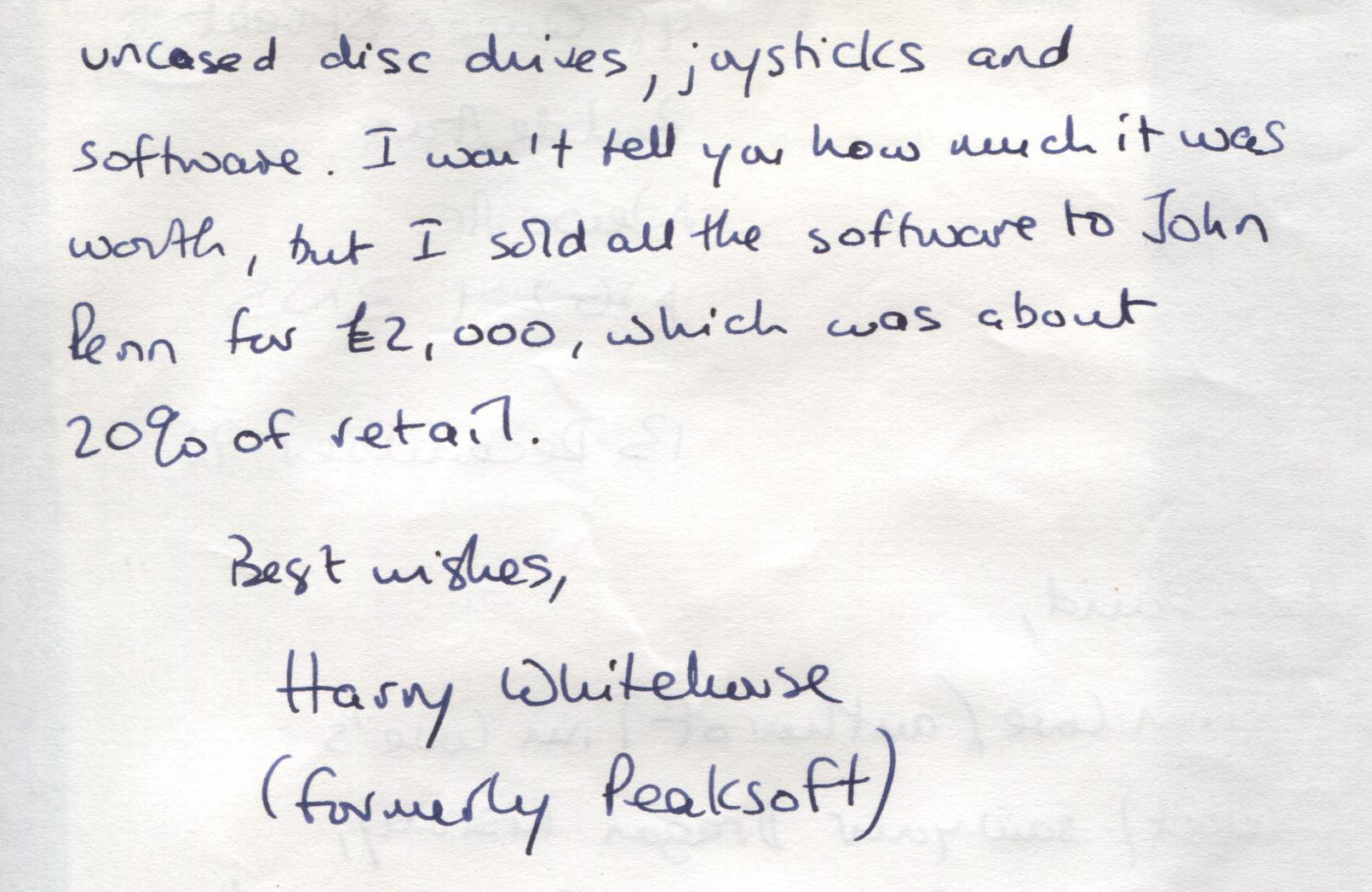

A letter from Harry to David Linsley, who wrote the potted history of

the Dragon and the primary subject of the letter. It also gives

insight into buying (at best guess) was the dead stock at

Touchmaster, left over from Dragon Data. Thanks to David for the

letter.

|

In common with many Basic programmers

before me, my first effort was an appalling hangman game, for which I

typed in a bank of 1,000 place names and 1,000 football topics. I had the

nerve to advertise it for £5.45 in Popular Computing Weekly and sold a few

copies. These were produced on the dining table with a Dragon and a

cassette recorder, then labelled with typewritten stickers.

In common with many Basic programmers

before me, my first effort was an appalling hangman game, for which I

typed in a bank of 1,000 place names and 1,000 football topics. I had the

nerve to advertise it for £5.45 in Popular Computing Weekly and sold a few

copies. These were produced on the dining table with a Dragon and a

cassette recorder, then labelled with typewritten stickers. Champions!

Champions! The cassette case insert had

a black and white Press photograph taken at Burton Albion's Southern

League ground.

The cassette case insert had

a black and white Press photograph taken at Burton Albion's Southern

League ground. The first cassette labels

were all hand-typed.

The first cassette labels

were all hand-typed.  Boots were the leading stockists of

Dragon computers, so I wrote to their head buyer. As a result, in November

1983 they ordered £27,000-worth of tapes from me. I bought a second Dragon

and set to work duplicating them. I sat up late at night, saving every

single ordered copy from those two computers. As I wasn't paying

professional duplicators, all but about £1,000 of that order was pure

profit.

Boots were the leading stockists of

Dragon computers, so I wrote to their head buyer. As a result, in November

1983 they ordered £27,000-worth of tapes from me. I bought a second Dragon

and set to work duplicating them. I sat up late at night, saving every

single ordered copy from those two computers. As I wasn't paying

professional duplicators, all but about £1,000 of that order was pure

profit. Tim had been on holiday in India. On the

long flight back, he began coding a game which I always regarded as a work

of genius, and which I called, quite simply, Tim Love's

Cricket.

Tim had been on holiday in India. On the

long flight back, he began coding a game which I always regarded as a work

of genius, and which I called, quite simply, Tim Love's

Cricket. This was soon solved, but not before my

wife, Maureen, and I began to dread the ringing of the telephone.

Everyone, it seemed, wanted to tell us that their ball was stuck on the

wrong side of the boundary.

This was soon solved, but not before my

wife, Maureen, and I began to dread the ringing of the telephone.

Everyone, it seemed, wanted to tell us that their ball was stuck on the

wrong side of the boundary. Having done that, he rewrote it for the

Amstrad CPC464. We had hoped to have a Spectrum version, but two separate

independent programmers wasted a lot of our time and eventually produced

nothing. Pictured is the insert card...ready for the game that was never

produced.

Having done that, he rewrote it for the

Amstrad CPC464. We had hoped to have a Spectrum version, but two separate

independent programmers wasted a lot of our time and eventually produced

nothing. Pictured is the insert card...ready for the game that was never

produced. When retail shop

sales virtually ended, I still continued selling by mail order through

football magazines, then I made a few thousand pounds more by licensing

Alternative Software to issue budget versions. They renamed it Soccer

Boss, and for one wonderful week, it was number 1 in the UK sales

chart.

When retail shop

sales virtually ended, I still continued selling by mail order through

football magazines, then I made a few thousand pounds more by licensing

Alternative Software to issue budget versions. They renamed it Soccer

Boss, and for one wonderful week, it was number 1 in the UK sales

chart.